Paleontologists Find Fossil of Ancient Vomited Amphibians

September 13, 2022

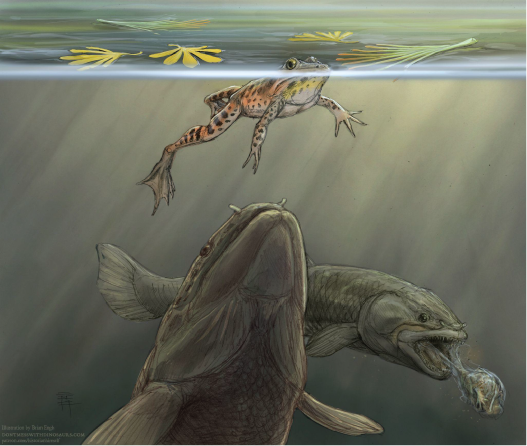

150 million years ago, in what is now southeastern Utah, a startled bowfin fish may have vomited up its recent meal of tadpoles and a salamander before escaping whatever had threatened it.

SALT LAKE CITY — A team of paleontologists from the Utah Division State Parks, the Utah Geological Survey and the Flying Heritage & Combat Armor Museum recently recovered a small fossil consisting of a pile of amphibian bones that appear to have been regurgitated by the predator that had ingested them. The fossil appeared among plant fossils at a site in southeastern Utah in rocks of the Morrison Formation, the same layer that produces the dinosaurs of Dinosaur National Monument.

Although the Late Jurassic-age Morrison Formation is famous for its dinosaurs, such as Stegosaurus and Brachiosaurus, it contains a diverse assemblage of other animals. Among those other animals are familiar beasts such as frogs, salamanders, and fish. Although the site in southeastern Utah is dominated by plant fossils, these amphibians and bowfin fish are also known from the site, which represents a pond deposit.

Aspects of this new fossil, relating to the arrangement and concentration of the bones in the deposit, the mix of animals, and the chemistry of the bones and matrix, suggested that the pile of bones was regurgitated out by a predator. The amphibian bones in the pile are tiny (some just 0.12 inches long) and include some of the smallest individual bones in the Morrison Formation. The shape, preservation, and size of the frog bones indicate that at least two individuals were present and that one may have been a tadpole; there appears to have been at least one salamander as well.

But what was the predator in this pond that ate the amphibians? Likely candidates in the Morrison Formation include fish, a semi-aquatic mammal, or perhaps turtles. Among these, only bowfin fish have yet appeared at the site.

“We can’t be sure, but among the animals of interest here, the current best match, and the one known to be at the scene, is the bowfin fish,” Utah Field House of Natural History State Park Museum Curator John Foster, co-author of the study. “Although we can’t rule out other predators, a bowfin is our current suspect, so to speak.”

Fish and other animals will sometimes vomit recent meal remnants when pursued, in part perhaps to distract their would-be predator.

“This fossil gives us a rare glimpse into the interactions of the animals in ancient ecosystems,” Foster said. “There were three animals that we still have around today, interacting in ways also known today among those animals – prey eaten by predators and predators perhaps chased by other predators. That itself shows how similar some ancient ecosystems were to places on Earth today.”

Fish, frogs and salamanders have been found in the Morrison Formation since the late 1800s. However, it isn’t the presence of these animals itself that is unusual about the new fossil. It is that the fossil documents a predator’s meal and that predator’s subsequent need, for whatever reason, to purge that meal rather suddenly. That is a first in the Jurassic rocks of North America.

The site where the regurgitated pile was found produces well-preserved plant fossils of a diversity of ginkgoes, ferns and conifers in a small pond or lake setting. The flora indicates a wetter and more lush setting for southeastern Utah at the time. Two years ago the same site also produced the giant water bug relative Morrisonnepa, only the second insect body fossil known from the formation.

“I was so excited to have found this site, as Upper Jurassic plant localities are so rare,” said study co-author Jim Kirkland of the Utah Geological Survey. “We must now carefully dissect the site in search of more tiny wonders in among the foliage.”

The study on the “fish-puked tadpole” — as it became somewhat facetiously known among the authors and their in-house colleagues — was recently published in the journal Palaios.

If you found this blog entry interesting, please consider sharing it through your social network.